Curaçao (True) Children’s Stories

Jan Gerard Palm

Jan Gerard Palm (1831–1906) took European music and reimagined it for the Caribbean. He listened not just to the notes — but to the people, the spaces, and the rhythm of life on the island making Curaçao a center of musical innovation for the region. Palm published his new arrangements in La Cruz, the island’s cultural magazine.

As a major port city what happened in Willemstad influenced the other islands within weeks. In Aruba, couples danced to his musical adaptions. In St. Maarten, students practiced it. In Colombia and Cuba, musicians sent letters asking for more.

The Music That Bumped the Walls

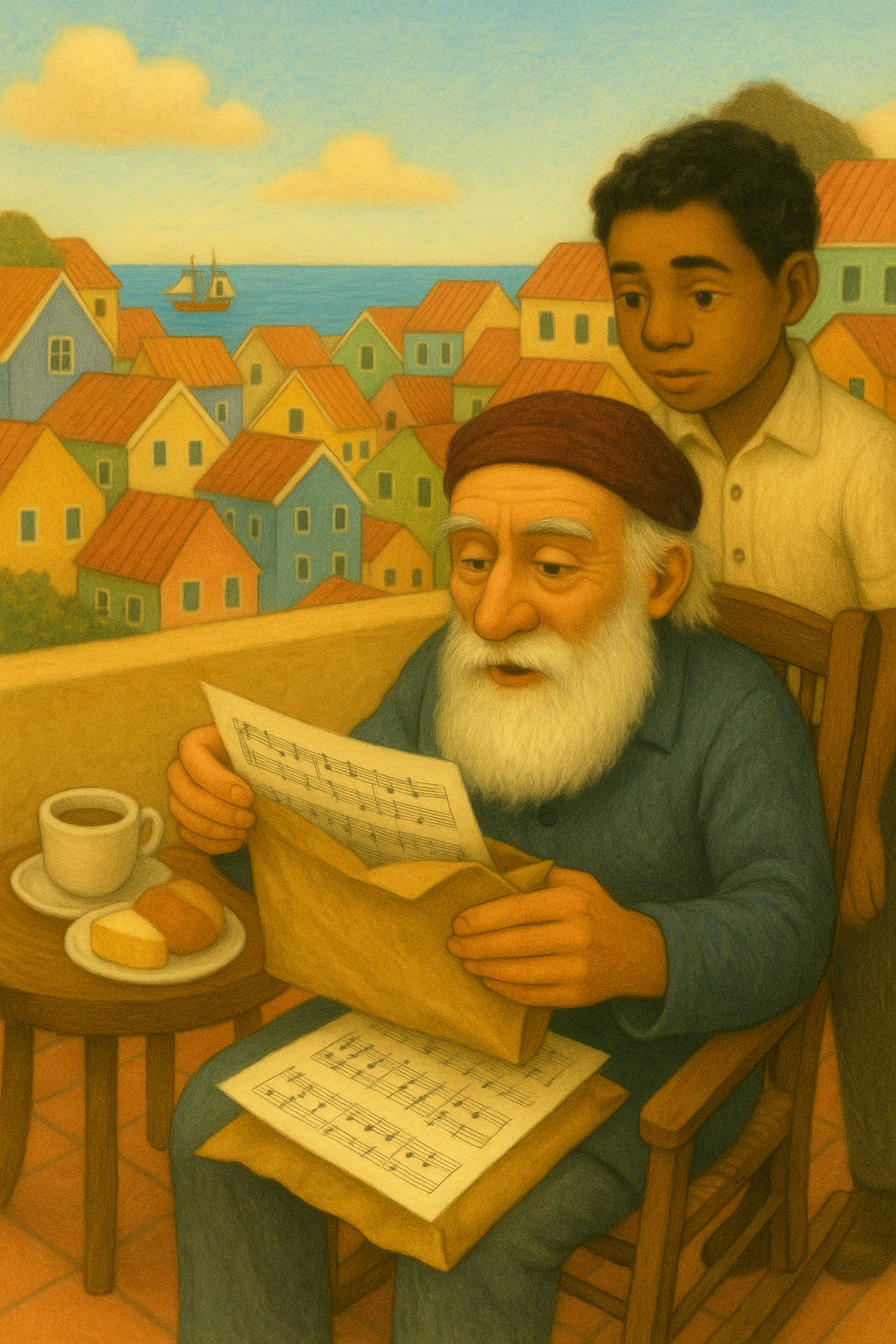

One morning in the city of Willemstad, Jan Gerard Palm was sitting on his porch, sipping coffee, when the postman arrived with a thick brown envelope. It was crinkled and smelled like salt. “Straight off the steamer from Amsterdam,” the postman said, handing it over the wall.

Palm opened it carefully. Inside were pages and pages of sheet music—waltzes, polkas, mazurkas—dances written by famous European composers.

His young friend, Jose, peered over his shoulder. “What does it sound like?”

“Very elegant,” Palm said. as he adjusted his whiskers around his mouth. "Humm, they like to spin and swirl in Europe.”

Jose imagined golden ballrooms, sparkling chandeliers, and ladies in swirling gowns. It all seemed very far away from the little houses of Willemstad, where goats clattered over cobblestones and sea breeze danced through blue shutters.

That Saturday night, the neighborhood squeezed into the family’s salon. It wasn’t a ballroom—just a room with a piano, a few chairs, and a crowd ready to dance.

Palm sat at the piano and began to play one of the waltzes.

At first, it was lovely. But the dancers didn’t make it through the first chorus.

They twirled too wide and bumped into the walls. A man tripped on a stool. A girl spun too fast and knocked over a vase of bougainvillea. The melody floated beautifully—but it didn’t fit. Not the room. Not the island. Not the way people moved in Curaçao.

Jose tugged on his Jan’s sleeve. “Maybe the music’s too big for here?”

Palm didn’t answer.

But that night, when the house was quiet, he lit a lantern, opened his sheet music, and sat down at his desk. The window was open. A dog barked in the distance. The pages rustled in the breeze. Willemstad was asleep. Palm stared at the notes.

The European composers had written their dances for grand halls—marble floors, tall ceilings, giant orchestras. But in Curaçao, rooms were small. Roofs were low. Parties were packed. Music, heat, and laughter all bounced off the walls.

He tapped his pencil. Then he began to make changes.

He quickened the tempo. Trimmed the twirls. Took out the pauses. Added a bit of tambú rhythm—a little sway instead of a spin. Now the music danced differently. It tapped like sandals on stone. It moved like the island moved.

It would fit.

The next evening, Palm sat at the piano once more. This time, the music flowed tighter, warmer, closer to home. The couples glided instead of twirled. They smiled instead of stumbled.

Jose clapped along. “It fits! It fits now!”

Palm nodded. “That’s because I listened.”

“Listened to what?”

“To the walls. To the room. To Curaçao.

Witch

The Sea Witch of Watamula